Agile Research

Applying the Agile Software Development Methodology to Your Doctoral Research Journey

Motivation

I recently commenced my doctoral journey, which I am doing part time alongside a full-time job, yes I am a glutton for torture! My cohort of fellow doctoral candidates comprises of seasoned professionals who’ve distinguished themselves as thought leaders in their respective fields.

In our initial discussions it became apparent that for most, the idea of conducting research and producing a thesis seemed daunting, the classic “What have I gotten myself into!” moment, owing to the sheer scale of the undertaking. Throw in balancing work and life commitments to the mix and you have the perfect recipe for an ulcer or two.

This blog is an attempt to help my batchmates and future researchers to apply the Agile Software Development methodology to their research to cope with the inevitable stress and uncertainty which accompanies the journey.

What is Agile, Really?

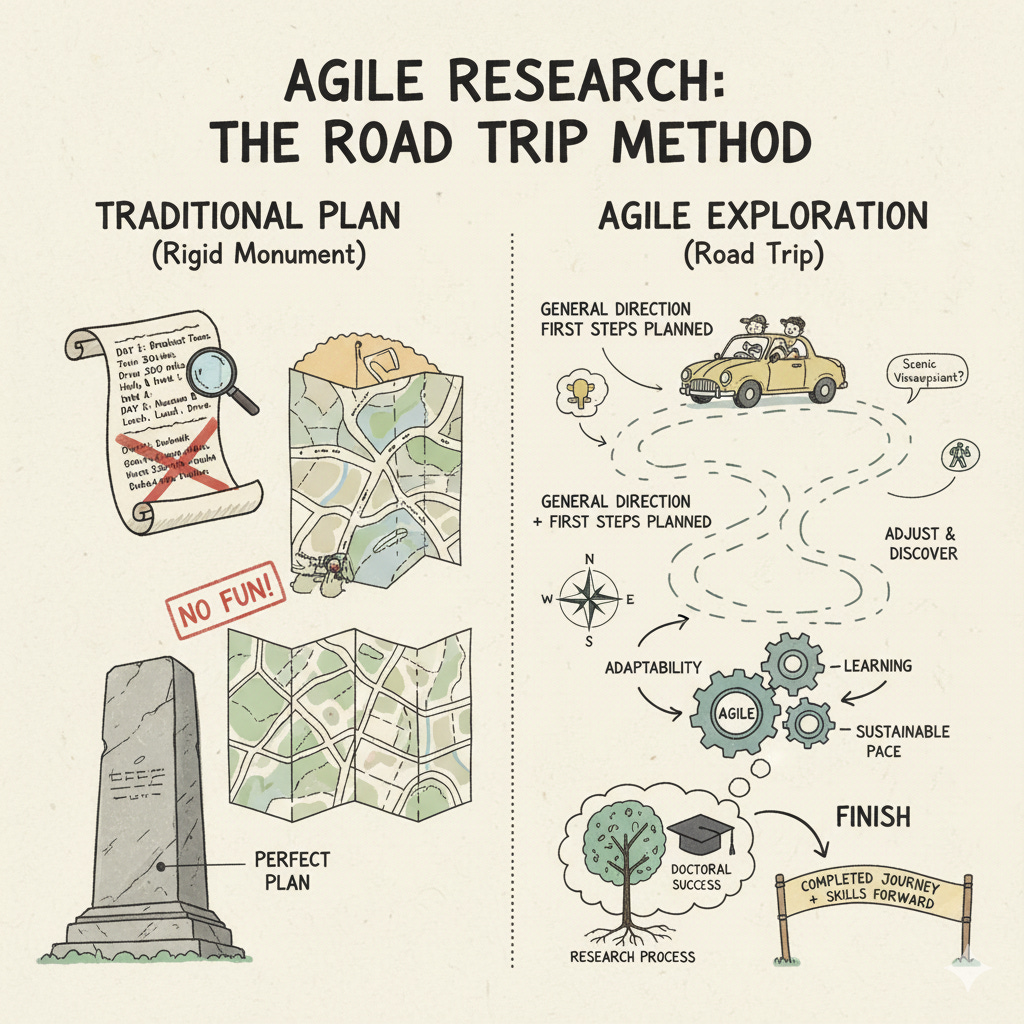

Imagine you’re planning a cross-country road trip. You could map out every single stop, meal, and hotel room before you leave, or you could set a general direction, plan the first few days in detail, and adjust as you discover interesting detours along the way. Agile methodology is like that second approach, but applied to creating software—or in your case, conducting doctoral research.

Agile emerged in the software world when teams realized that trying to plan everything upfront often led to frustration. Requirements changed, new discoveries emerged, and rigid plans became obstacles rather than guides. Instead, Agile teams work in short cycles, regularly check their progress, adapt to new information, and stay focused on delivering value incrementally.

You might wonder how a method designed for software developers could possibly help with academic research. After all, research feels different—it’s exploratory, unpredictable, and deeply intellectual. But here’s the insight that makes Agile so powerful for doctoral work: research is exactly as unpredictable as software development, just in different ways. Literature reviews reveal unexpected gaps, experiments produce surprising results, and theoretical frameworks evolve as you understand your field more deeply.

Why Agile Fits Doctoral Research

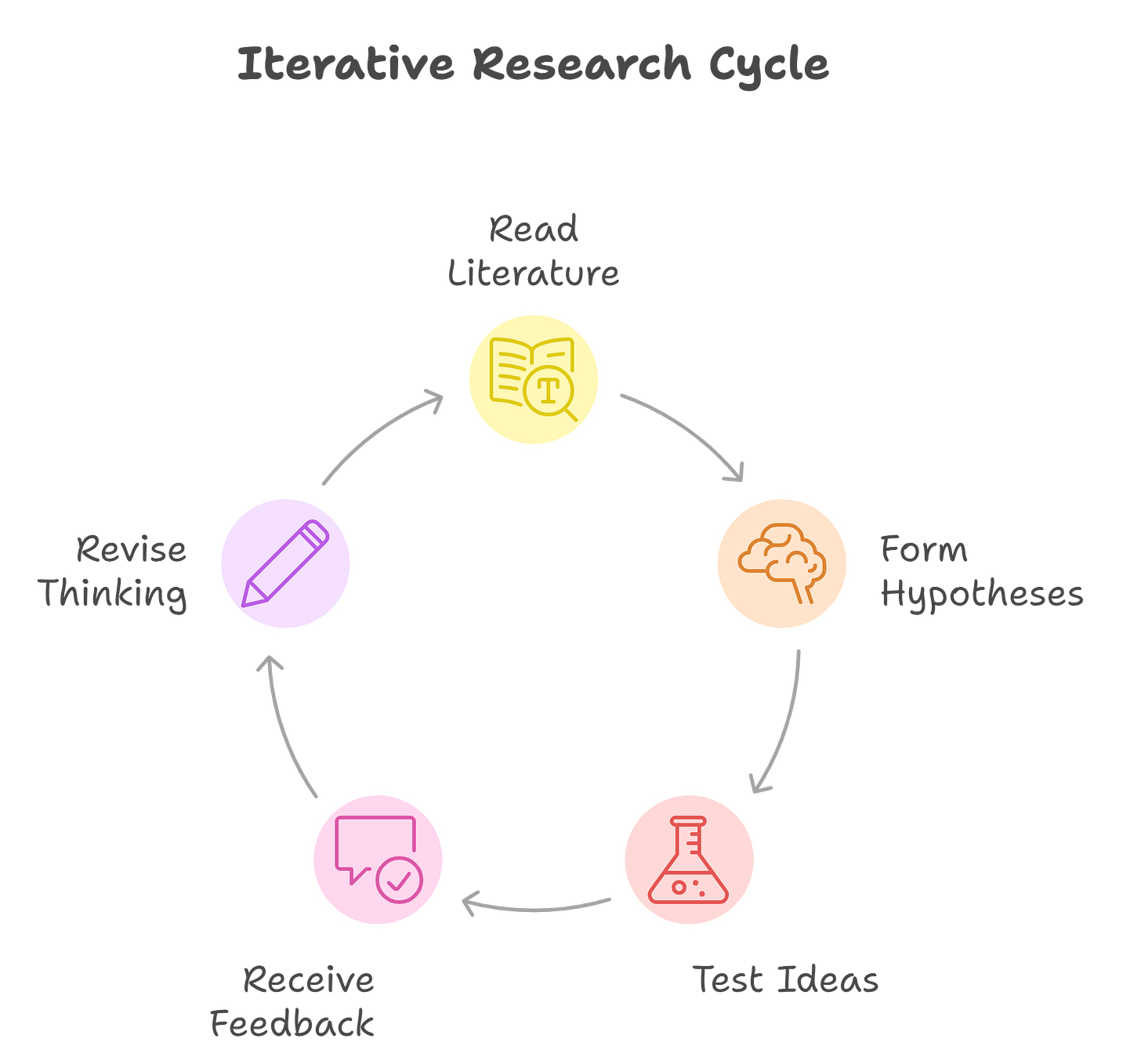

Doctoral research already happens iteratively, even if we don’t always acknowledge it. You read literature, form hypotheses, test ideas, receive feedback from your advisor, revise your thinking, and repeat. The problem is that without a structured approach, this iteration can feel chaotic and overwhelming. You might spend months going down rabbit holes, struggle with scope creep as your thesis expands uncontrollably, or lose momentum when the finish line seems impossibly far away.

Agile provides the missing structure. It gives you a framework for managing uncertainty, breaking overwhelming projects into manageable pieces, and maintaining steady progress even when the path ahead isn’t perfectly clear. Most importantly, it helps you stay responsive to feedback and new discoveries without derailing your entire project.

Core Agile Principles for Doctoral Candidates

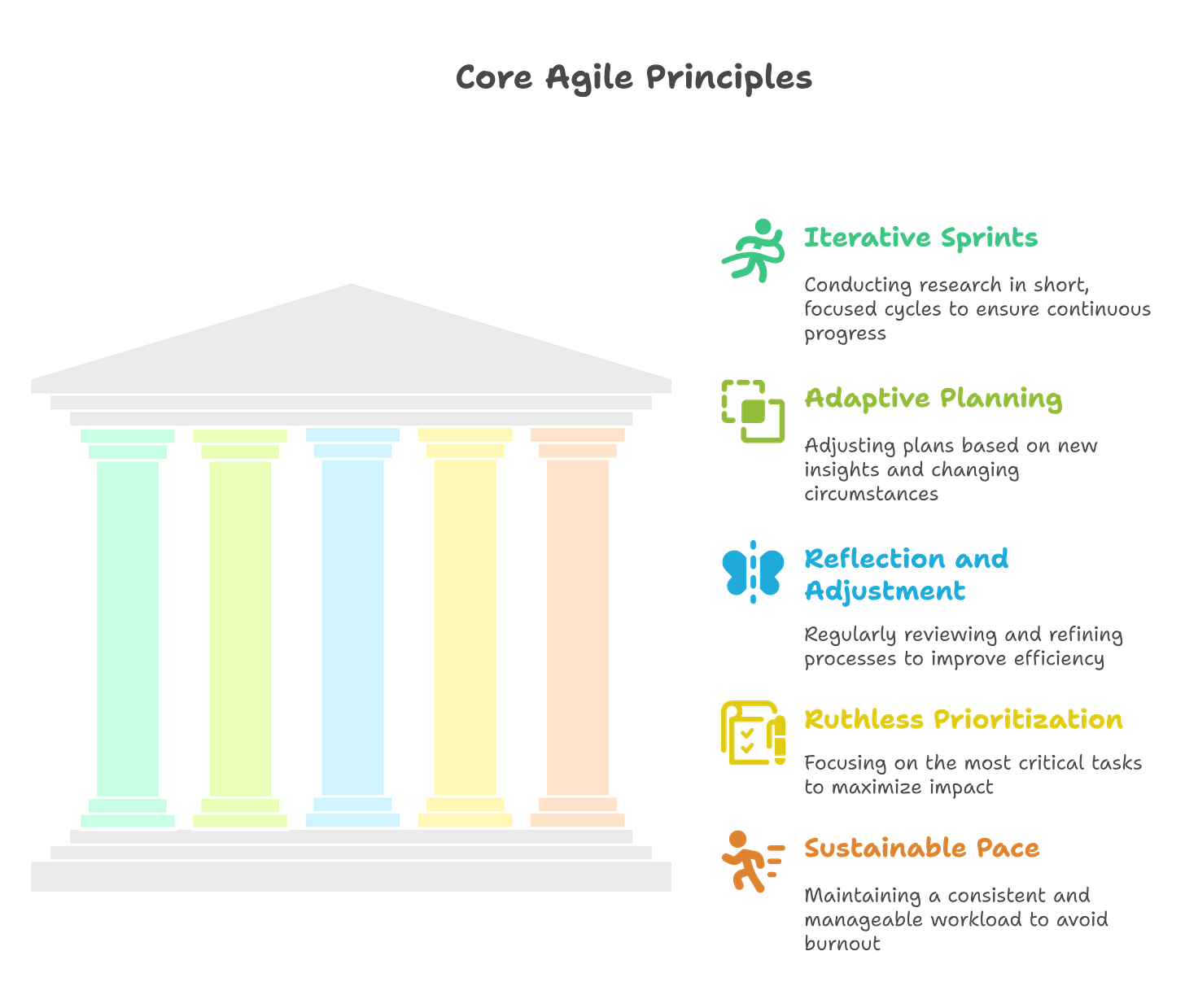

Before we explore specific applications, let’s understand the fundamental principles that make Agile work. Think of these as the philosophical foundation that will guide your research approach.

Working in Iterations (Sprints)

In Agile, work happens in short, focused cycles called “sprints”—typically one to four weeks long. Each sprint has clear goals, and at the end, you have something tangible to show for your efforts. For doctoral research, this means breaking your multi-year journey into two-week or monthly cycles, each with specific, achievable objectives.

Consider Maria, a doctoral candidate studying climate policy. Instead of thinking “I need to complete my literature review,” she plans a two-week sprint with the goal: “Identify and synthesize fifteen key papers on carbon pricing mechanisms in developing nations.” At the end of two weeks, she has a concrete deliverable—a synthesis document—rather than just feeling like she’s “still reading.”

Embracing Adaptive Planning

Agile teams plan continuously rather than just at the beginning. They create detailed plans for the immediate work ahead and keep longer-term plans deliberately flexible. For your doctoral research, this means having a detailed plan for the next month, a sketch for the next quarter, and a general direction for the next year—not a rigid timeline carved in stone for all five years.

James is researching neural networks in artificial intelligence. When a groundbreaking paper is published that challenges his initial assumptions, he doesn’t panic. His adaptive planning approach means he’s prepared for such shifts. He adjusts his next sprint to incorporate this new direction while his broader thesis structure remains intact.

Regular Reflection and Adjustment

Agile teams hold “retrospectives” where they ask: What went well? What didn’t? What should we change? This habit of structured reflection transforms experience into wisdom. After each research sprint, you’ll assess not just what you accomplished, but how efficiently you worked, what obstacles slowed you down, and how you can improve your process.

Prioritizing Ruthlessly

In Agile, teams constantly ask, “What’s the most valuable thing we could work on right now?” This question is particularly powerful for doctoral candidates who face infinite possible directions. Every week, you’re choosing between reading more literature, refining your methodology, collecting data, writing, or seeking feedback. Agile prioritization helps you make these choices strategically rather than randomly.

Maintaining a Sustainable Pace

Agile explicitly rejects the idea that working longer hours equals better results. Sustainable pace recognizes that quality work requires rest, reflection, and a life beyond the project. For doctoral candidates, who often fall into cycles of burnout and guilt, this principle provides permission—indeed, insistence—to work in a way that you can maintain for the long journey ahead.

Applying Agile to Your Research Stages

Now let’s explore how these principles translate into concrete practices at each stage of your doctoral journey.

Initial Research and Scoping Phase

When you first begin your doctoral work, everything feels simultaneously exciting and overwhelming. You’re identifying your research question, understanding your field’s landscape, and figuring out what’s actually feasible within your time and resource constraints.

Agile approach: Create a “research backlog”—a living list of all potential activities, questions, and directions you might pursue. Think of this as a brain dump of possibilities. Then, organize these items by priority and uncertainty. Your highest priorities are things that will help you make critical decisions about your research direction.

For example, Aisha is beginning research on food security in urban environments. Her initial backlog includes items like “Review major food security frameworks,” “Interview three urban planners,” “Map existing community garden initiatives in target city,” and “Explore potential data sources for food access metrics.” She doesn’t try to do everything at once. Instead, she picks the highest-priority items for her first two-week sprint: reviewing frameworks and conducting preliminary interviews. These activities will inform everything else, so they come first.

Sprint planning in this phase: Your sprints focus on reducing uncertainty. Each sprint should answer key questions that will shape your research design. You might spend one sprint exploring methodological options, another testing whether you can access critical data sources, and another examining whether your initial research question is actually feasible and original.

Concrete practices: Set up a simple system to track your backlog. This could be as simple as a spreadsheet with columns for “Task,” “Priority,” “Estimated Time,” and “Status.” Before each sprint, select a realistic amount of work—remember, you’re learning what “realistic” means for you, so start conservatively. At the end of each sprint, review what you accomplished and adjust your backlog based on what you learned.

Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

The literature review is where many doctoral candidates lose momentum. It’s easy to feel like you can never read enough, or to keep discovering new relevant areas that expand your scope endlessly.

Agile approach: Treat your literature review as an iterative deepening process rather than an attempt at comprehensive coverage from day one. Start with a “minimum viable literature review” that covers the essential foundations, then expand strategically based on what your research actually needs.

Consider Marcus, studying organizational change in healthcare settings. His first literature sprint focuses narrowly on foundational theories of organizational change—the classics everyone cites. Sprint two explores healthcare-specific applications. Sprint three dives into the particular type of healthcare organization he’s studying. Each sprint builds on the previous one, and at any point, he has a coherent literature foundation even if it’s not yet complete.

Sprint structure for literature work: A typical two-week literature sprint might include identifying relevant papers (days 1-2), reading and annotating them (days 3-8), synthesizing key themes and gaps (days 9-11), and writing a synthesis document (days 12-14). The key is that each sprint produces written output, not just a stack of highlighted papers.

Concrete practices: Create a literature database as you read—a spreadsheet tracking each source with columns for key arguments, methodology, relevant findings, and how it relates to your work. Set a cap on how many papers you’ll review per sprint (perhaps 10-15 depending on their length and density). When you discover a new relevant area, add it to your backlog rather than immediately diving in. This prevents the endless expansion that derails many literature reviews.

Methodology Development and Pilot Studies

Developing your methodology is inherently iterative. You rarely get your research design perfect on the first attempt—and Agile’s iterative nature makes this explicit rather than something to feel ashamed about.

Agile approach: Plan your methodology development in progressive stages. Start with a minimal version, test it, learn from what doesn’t work, refine, and repeat. This is analogous to how Agile software teams build a “minimum viable product” and then enhance it based on user feedback.

Sofia is developing a mixed-methods study on teacher retention. Her first methodology sprint involves designing a pilot interview protocol with five questions and conducting two pilot interviews. She doesn’t try to create the perfect 30-question protocol upfront. Instead, she tests a minimal version, discovers that her questions aren’t eliciting the depth of response she needs, and adjusts before investing in 50 full interviews.

Sprint structure for methodology: Early sprints focus on design and small-scale testing. You might spend one sprint drafting your interview protocol or survey instrument, another conducting pilot tests with three to five participants, and a third analyzing those pilot results and refining your approach. Only after this iteration do you commit to full-scale data collection.

Concrete practices: Document your methodology evolution. Keep a methods journal where you record what you tried, what worked, what didn’t, and why you made changes. This documentation becomes invaluable when you write your methodology chapter and need to justify your choices. Schedule explicit “test and learn” sprints where the goal isn’t to collect final data but to refine your approach.

Data Collection

Data collection often feels like it needs to happen all at once—a single, massive push. But Agile teaches us to collect data in waves when possible, learning from each wave before committing fully to the next.

Agile approach: Phase your data collection into increments. Collect some data, do preliminary analysis, verify you’re getting what you need, adjust if necessary, then collect more. This protects you from discovering after six months of data collection that you were asking slightly the wrong questions or missing a critical variable.

Daniel is conducting a quantitative study requiring survey data from multiple organizations. Instead of sending his survey to all twenty organizations at once, he runs it with three organizations first. During the preliminary analysis sprint that follows, he discovers that one of his key questions is consistently misunderstood. He refines the question for the remaining seventeen organizations, saving his entire dataset from a fundamental measurement problem.

Sprint structure for data collection: Alternate between collection sprints and analysis sprints. A collection sprint might involve conducting five interviews or distributing surveys to one organizational unit. The following sprint focuses on preliminary coding or statistical analysis of that data. This rhythm ensures you’re constantly verifying that your data collection is on track.

Concrete practices: Set measurable targets for each collection sprint: “Complete eight interviews,” “Survey 200 participants,” or “Collect three months of observational data.” Track your progress visibly—perhaps a chart showing interviews completed versus planned. Build in buffer time because data collection rarely goes exactly as scheduled. When participants cancel or response rates are lower than expected, having a sprint-by-sprint view helps you adjust timelines realistically.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analysis is where your research truly takes shape, and it’s inherently iterative. You explore patterns, test interpretations, reconsider your frameworks, and gradually build your argument.

Agile approach: Analyze in layers, starting broad and progressively narrowing to deeper insights. Your first analysis sprint might focus on basic descriptive patterns. The next might explore relationships between variables. Subsequent sprints dive into specific puzzles or surprising findings. Each layer of analysis informs the next, and you’re building toward your contribution incrementally.

Rachel is analyzing interview transcripts about workplace mentorship. Her first analysis sprint involves open coding five transcripts to identify emerging themes. Sprint two applies those themes to ten more transcripts, testing whether the framework holds or needs adjustment. Sprint three focuses specifically on the surprising pattern she noticed—that formal mentorship programs sometimes undermine informal mentoring relationships. By sprint four, she’s developing the theoretical interpretation that will become a key contribution of her thesis.

Sprint structure for analysis: Early sprints are exploratory and generative. Middle sprints are focused on specific research questions or hypotheses. Later sprints are integrative, connecting findings back to your literature and building your argument. Each sprint should produce a written artifact—even if it’s rough notes—that captures your thinking.

Concrete practices: Create an analysis plan at the start of each sprint: “This sprint, I will code transcripts 10-20 focusing on the theme of institutional barriers” or “This sprint, I will run regression models testing the relationship between variables X and Y, controlling for Z.” Keep an analysis log documenting decisions about coding, categorization, or statistical approaches. When you make a choice that could affect your conclusions, write down why you made it. This becomes essential material for your methods and analysis chapters.

Writing and Synthesis

Writing your thesis happens throughout your research, not just at the end. Agile’s emphasis on producing tangible outputs each sprint naturally integrates writing into your ongoing work.

Agile approach: Write continuously in small increments rather than waiting until everything is “ready.” Each sprint produces some written output—a literature synthesis, a methods description, a findings section, or an analytical memo. These pieces eventually become your thesis chapters, but they’re written when the ideas are fresh rather than recreated from memory years later.

Thomas follows a pattern where every analysis sprint includes writing time. He doesn’t wait until all analysis is complete. After each analysis increment, he spends the last two days of the sprint writing up what he found. These writing pieces are rough—full of brackets where he needs to add citations, and notes to himself about interpretations to develop further. But by the time he reaches his “writing phase,” he has 30,000 words of rough draft material to revise rather than facing a blank page.

Sprint structure for writing: Some sprints are dedicated primarily to writing—perhaps when you’re working on your introduction or discussion chapters. But most sprints integrate writing with other activities. A typical pattern might be: first half of sprint on analysis or reading, second half synthesizing those findings in writing. As you near completion, you’ll have more writing-focused sprints dedicated to revision, integration, and polish.

Concrete practices: Set word count goals for writing sprints, but measure “finished draft” words, not perfect prose. A realistic goal might be 1,000 words per day on days dedicated to writing. Create templates for common sections you’ll write repeatedly (like literature synthesis paragraphs or findings sections) to speed up drafting. Most importantly, separate drafting from editing. In a drafting sprint, you write without stopping to perfect every sentence. Editing sprints come later.

Feedback Integration and Revision

Regular feedback is central to Agile, and it’s equally crucial for doctoral research. However, academic feedback can be overwhelming—detailed, critical, and sometimes contradictory. Agile practices help you process and integrate feedback systematically.

Agile approach: Schedule regular feedback cycles into your sprint plan. After every few sprints of focused work, you have a “feedback sprint” where you share progress with your advisor, get input, and plan adjustments. This creates rhythm and expectation rather than random, anxiety-producing feedback exchanges.

Yuki meets with her advisor every three weeks. She plans her sprints around this schedule. Sprints one and two focus on making progress, and she prepares a summary document showing what she accomplished and what questions she has. Sprint three is lighter on new work and heavy on integrating feedback, adjusting her backlog, and planning next steps. This rhythm means her advisor sees steady progress, and she has dedicated time to thoughtfully respond to feedback rather than feeling perpetually behind.

Sprint structure for feedback: A feedback integration sprint might look like this: Day 1-2, review all feedback and categorize it (major revisions needed, minor clarifications, future considerations). Days 3-4, prioritize changes and add them to your backlog. Days 5-10, implement high-priority changes. Days 11-14, plan upcoming sprints with these adjustments in mind.

Concrete practices: Maintain a feedback log where you track all suggestions from your advisor, committee members, or peer reviewers. Note each piece of feedback, your interpretation of it, the action you plan to take, and when you completed it. This serves multiple purposes: it ensures nothing falls through the cracks, it helps you see patterns in feedback over time, and it documents your responsiveness for your committee.

Integration and Thesis Completion

The final phase brings everything together—integrating your chapters, writing introduction and conclusion chapters, and preparing for defense. This is where many candidates feel overwhelmed by the sheer scope of material to synthesize.

Agile approach: The beauty of having worked in sprints with regular written outputs is that you don’t face a blank page at the end. Instead, you have a collection of rough chapters and substantial written material. Your completion phase involves integration, refinement, and ensuring coherence across chapters rather than generating content from scratch.

Fatima begins her integration phase with a systematic review sprint. She reads through all her chapter drafts as a reader would, taking notes on themes that need to be strengthened, arguments that need clarification, and connections between chapters that should be made explicit. Her next sprint focuses on her introduction chapter, using insights from this review. Subsequent sprints tackle one chapter at a time, revising for coherence, completeness, and clarity.

Sprint structure for completion: These sprints are more writing-intensive than earlier phases. A typical sprint might focus on one chapter, with the goal of bringing it from rough draft to complete draft. You might spend one sprint on methodology, another on a findings chapter, another on the discussion. Intersperse intense writing sprints with editing and formatting sprints to maintain sustainable pace and give your brain different types of work.

Concrete practices: Create a completion checklist that breaks your thesis into every component that needs attention: abstract, acknowledgments, table of contents, each chapter, appendices, formatting, references, and so on. Use sprints to systematically work through this list. Schedule at least one full-thesis review sprint where you read the entire document start to finish, checking for narrative flow and coherence. Build in buffer sprints for unexpected complications—they will happen, and planning for them reduces stress.

Practical Tools and Techniques

To implement Agile effectively, you need simple tools that support your process without becoming burdensome.

Sprint planning tools: You don’t need fancy project management software. A simple spreadsheet with columns for “Sprint Dates,” “Goals,” “Planned Tasks,” and “Completed Tasks” works well. Or use a notebook with each two-page spread representing one sprint. The key is visibility—you should be able to see at a glance what you’re committing to for the current sprint.

Backlog management: Your research backlog is your evolving to-do list. It includes everything you might do, organized by priority. Review and reprioritize it before each sprint. As new ideas or requirements emerge, add them to the backlog rather than immediately acting on them. This gives you control over scope creep—you’re not saying no to good ideas, just “not right now.”

Daily or weekly check-ins: In Agile, teams have brief daily check-ins to maintain alignment. For solo doctoral work, this might be a weekly self-check-in: What did I accomplish this week? What’s my focus for the coming week? What obstacles am I facing? Writing this down in a research journal creates accountability and helps you spot patterns.

Retrospectives: At the end of each sprint, spend thirty minutes reflecting. What went well? What didn’t work as planned? What will I do differently next sprint? This single habit transforms your experience into systematic improvement. Maybe you discover you’re most productive writing in the morning, or that you consistently underestimate how long data cleaning takes. These insights make each sprint more effective than the last.

Visualization of progress: Create simple visual representations of your progress. This might be a chart showing chapters completed, data collected, or papers reviewed. Having a visual sense of progress is motivating and helps you communicate with advisors or funders about where you are in your journey.

Maintaining Momentum and Managing Challenges

Even with good structure, doctoral research is challenging. Agile practices help with common problems, but they don’t eliminate difficulty—they just make it more manageable.

When sprints don’t go as planned: This will happen often. Data collection takes longer than expected, readings are denser than anticipated, or life intervenes. The Agile response isn’t guilt but adjustment. When a sprint goes off track, reflect on why, adjust your backlog and next sprint plan, and move forward. Each failed sprint is data about what’s realistic.

When you lose motivation: Doctoral work is long enough that everyone faces periods of low motivation. Agile’s short sprint cycles help here—even when you can’t imagine finishing your thesis, you can imagine finishing this two-week sprint. Focus on the immediate, concrete goal. Small, consistent progress accumulates into major achievements.

When feedback is overwhelming: Sometimes advisor feedback seems to require reworking everything. Before panicking, use a feedback integration sprint to really understand what’s being asked. Often, seemingly large changes can be broken into smaller, manageable pieces. Prioritize: what absolutely must change, what would strengthen the work if changed, and what can be noted for future consideration? Add changes to your backlog and tackle them systematically.

When the scope expands: Research naturally wants to grow. Every literature search reveals new relevant areas. Every analysis suggests new questions. Agile’s backlog system helps manage this. When you identify something interesting but not essential, add it to your backlog with a “nice to have” priority rather than immediately pursuing it. This acknowledges the idea without derailing your core work.

Conclusion: Research as a Series of Informed Steps

The traditional view of doctoral research imagines a straight line from question to conclusion, planned comprehensively at the start and executed without deviation. This has never matched reality—research has always been iterative, adaptive, and full of surprises. What Agile methodology offers is an honest framework that acknowledges this reality and provides structure for navigating it effectively.

By working in sprints, you transform an overwhelming multi-year journey into a series of manageable two-week challenges. By maintaining a prioritized backlog, you channel the chaos of infinite possibilities into intentional choices. By reflecting regularly, you get better at research not through luck but through systematic learning from experience. And by producing tangible outputs continuously, you maintain momentum and avoid the paralysis of perfectionism.

Your doctoral thesis is not a monument you must conceive perfectly in advance and then construct according to unchanging blueprints. It’s an exploration, a learning journey, and a conversation with your field. Agile gives you tools to navigate that journey with intention, adaptability, and sustainable effort. The result is not just a completed thesis, but a research process you can refine and carry forward into your academic career.

Start with small steps. Try a two-week sprint focused on a single, clear goal. At the end, reflect on how it felt and what you learned. Adjust your approach, and try another. Sprint by sprint, reflection by reflection, you’ll find a rhythm that works for your research, your temperament, and your life. The thesis awaits, not as an insurmountable mountain, but as a series of purposeful steps—each one manageable, each one bringing you closer to completion.

Well drafted methodology Clarence. I would like to sincerely commend you for integrating Agile methodology so thoroughly and thoughtfully into your Doctorate research. Your work not only demonstrates a deep understanding of Agile principles, but also showcases how adaptable and relevant they can be within the research-intensive context.

Your ability to bridge the gap between iterative, collaborative frameworks and the structured demands of scholarly research is truly impressive. By applying Agile in our doctoral journey—whether in managing timelines, incorporating continuous feedback, or adapting the research direction—you’ve provided a practical model for others who seek flexibility without compromising methodological rigor.

Your contribution is valuable not just for your field of study, but also for the broader research community, where Agile thinking is increasingly important in navigating complexity and change. Well done on bringing innovation to both methodology and mindset.